|

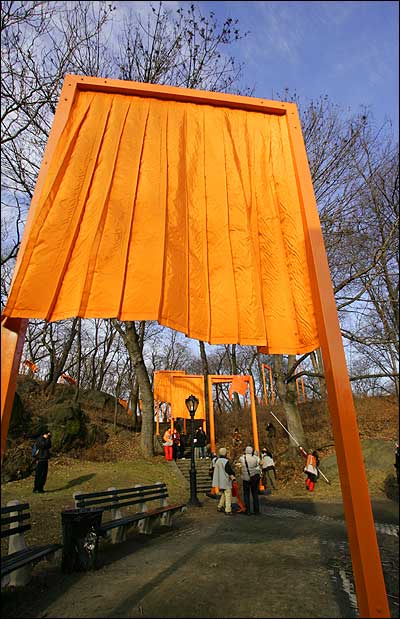

New York Architecture Images- Central Park Christo's Gates |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

artists |

Christo and Jean-Claude | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

location |

Central Park | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

date |

February 2005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

type |

Sculpture | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Torii Gates |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With thanks to www.christojeanneclaude.net |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

NY1

February 16, 2005 The Gates In Central Park Are Vandalized  After a grand unveiling over the weekend, “The Gates” in Central Park have apparently been vandalized. Some graffiti was reportedly found on one of the gates, and pieces of the fabric were cut as well. No arrests have been made. But the artists, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, did not seem bothered when they heard of the vandalism. “We don’t react,” said Jeanne-Claude. “We are not reactors; we are creators.” Over 7,500 gates draped with flowing saffron-colored fabric have been erected over 23 miles of pathways in Central Park to create the largest public artwork in the city’s history. “The Gates” will be up through February 27. Copyright © 2005 NY1 News |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

February 17, 2005

Young Critics See 'The Gates' and Offer Their Reviews: Mixed By JULIE SALAMON  Bella, 9, and Samuel Glanville, 11, visitors from London. Samuel uses terms like Fauvism and Pointillism. For Kate Rosenberg, 9, a third-grade student at Rodeph Sholom, a private school on the Upper West Side, the saffron-colored gates dreamed up by the artist Christo and his wife, Jeanne-Claude, have altered her vision of Central Park. "Before I didn't really look at the park," she said. "I didn't see how beautiful it is. "These gates, and there are billions of them, make me feel I will not look at the park the same way again." There are actually 7,532 gates spread along 23 miles of the park's pathways - not quite billions, but more than enough to loom large in a child's imagination. And in the opinion of some children, far too many. Perhaps especially in New York, it is never too soon to become a critic. Many youngsters wondered if this was art at all, and if it was, did it have to cost $21 million? "They just wasted their money on nothing," declared Ikim Powell, 10, who attends P.S. 368 in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn. "They should at least have paintings behind them." His classmate, Tyre Brooks, felt "The Gates" was an unnecessary artificial imposition on the park's natural beauty. "Now it looks like a stage, like on wrestling," he said. "I just want to ride my bike and play. I'd like to come back to the park when the flags aren't here. They look cheap." But another student from P.S. 368, Tyquam Nimmons, on his first visit to Central Park, disagreed. "It is artistic," he said. "There are a lot of them all around, and they're the same color and they give me a good feeling." He was about to elaborate but instead ran off to catch a football being tossed around by a group from his school. Martha Epstein, a Rodeph Sholom third-grader, sitting with her classmates on a hill made of boulders, had just finished a sketch of one of the gates. "This is about my millionth time seeing 'The Gates,' " she sighed. She said she was not much impressed on her first visit last weekend with her family, right after the 116,389 miles of saffron fabric were unfurled. "It was really crowded and I didn't like the orange," she said. "I wished it was green, a park color." Subsequent visits have somewhat altered her view. "I don't like the look of them but I like the way everybody is at the park and happy," she said. Lucinda Gresswell brought her two children to New York from London for their midterm break, in part because the Christo gates would be up. In the 1970's, Ms. Gresswell's father had bought a Christo drawing of either a pyramid or a sphinx, she could not remember which. So two weeks ago she booked a flight. Her 11-year-old son, Samuel Glanville, had no doubt that the gates were art. "Art is Fauvism, Pointillism, abstract," he said, looking at rows of pleated nylon fabric floating slightly at the whiff of a breeze. "This is Christo - is that his name, I forget? - this is his art, his own interpretation." Samuel liked knowing that "The Gates" would be on view for only two weeks. "Like all art, if it's always there it doesn't feel so special," he said, with the savvy of a shrewd museum director. "It's like a special Matisse show at a museum. You feel lucky if you get to see it." For his 9-year-old sister, Bella, on her first visit to New York, confronting "The Gates" was another in a series of crucial discoveries: the brilliant lights of Times Square, and Century 21, the bargain store near ground zero, where Bella acquired the very cool shirt she was wearing. She was not as certain as her brother of the artistic merit of the gates. "Well, yeah," she said, when asked if they were art. Then, she amended. "Not so much," she said. "They're kind of like flags. I prefer messy art, like blobs." But she was happy that Christo's project helped lure her family to Central Park, where she and Samuel worked up a healthy glow climbing on the rocks. "It wouldn't be too ordinary even without the flags," she said. "Most parks have grass and trees, not rocks. In England, unless it's a heath, you wouldn't have big rocks and stones." Sean Springer, a student from the Rhode Island School of Design on leave to work as a volunteer for "The Gates," said he had learned from the school groups wandering through. "There was an English class writing about their feelings, and I was wondering about the connections between literature and this work," he said. "My opinion is the art makes a poetic statement, and they said art is a form of poetry." Mr. Springer helped install "The Gates," will help take it down, and stands at the ready to untangle fabric with a pole capped by a tennis ball. He also answers questions and hands out swatches of the nylon saffron fabric to passers-by. "That's one thing that's the same for kids and adults," he said. "If they know about the swatches, they want them."  A student records impressions of "The Gates." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

February 17, 2005

In City of Ads, 'The Gates' Stand Apart By DAVID W. DUNLAP NOT a word. That may be one of the greatest gifts of "The Gates" to New York City: a sponsor-free public installation in Central Park. At a time when the civic realm is blanketed with corporate promotion, from lampposts to landmarks, the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude have shown that it is possible to hang 1,067,330 square feet of nylon in the heart of Manhattan - almost 50 acres of potential display space - without a slogan, trademark or logo. "I would have had a much more difficult time going to community boards, the Municipal Art Society and other civic groups making a case for it if there had been corporate logos on it," said Adrian Benepe, the parks commissioner. The artists are paying the estimated $21 million cost of the 16-day installation. They refuse sponsors, they say, because they want to work "in total freedom." Of course, in one sense, their work promotes themselves. Whether on the gray smocks worn by monitors along the walkways or in the piles of merchandise at the gift shops, there is no mistaking who gets top billing: Christo and Jeanne-Claude. But the couple are not trying to sell real estate or financial services, airline or museum tickets. To the extent that they may be trying to move "Gates" merchandise - or at least to satisfy the demand for it - they are not receiving income from the sales, which largely benefit city parks, said Megan Sheekey, a spokeswoman for the project. And the 16-foot-high orange gates are free of advertising. "There is not one image stamped on it," marveled Vanessa Gruen, director of special projects at the Municipal Art Society. "We're so used to seeing that kind of fabric used to drape buildings and for huge signs." For instance, the society has criticized as "obnoxious" a billboard modeled on a $10 bill that temporarily covers the front of the landmark New-York Historical Society on Central Park West, promoting the Alexander Hamilton exhibition. Another landmark near the park, the former United States Rubber Company Building at Broadway and 58th Street, now partly cocooned in scaffolding, has been turned into a temporary advertising kiosk for Independence Air. Around the park itself are dozens of three-by-eight-foot lamppost banners maintained by NYC & Company, the city's tourism marketing organization. Some currently feature paintings of dancers by Susan Rothenberg. These come emblazoned with the logo of the financial service firm UBS, in connection with a show at the Museum of Modern Art. Other banners along Central Park South are more like pure advertising. They show the logo of the real estate company CB Richard Ellis under a picture of Times Square with the legend "Real Estate Capital of the World." Cristyne L. Nicholas, the president and chief executive of NYC & Company, said banners around the city generate about $600,000 a year for the nonprofit organization, which in turn helps promote cultural institutions and events. "As far as corporate logos," she said, "that pays for the program, so that's necessary. All public art projects can't be funded by the generosity of Christo and Jeanne-Claude." Through the CVJ Corporation, of which Jeanne-Claude is president, the couple finance their projects by selling drawings, models, studies, lithographs and other artwork. TO date, more than 1 million visitors have viewed "The Gates," Ms. Sheekey said. You would think some corporation would salivate at this prospect, maybe one whose graphic identity is dominated by the color orange - like Home Depot or the ING Group - or one whose products might be conjured in viewers' minds by billowing curtains or rivers of orange, like the Coca-Cola Company (Minute Maid and Fanta) or Procter & Gamble (Downy fabric softener). "In other projects, we have received offers of sponsorship and have always said a flat no," Jeanne-Claude said in a telephone interview on Tuesday. "But for 'The Gates,' we have not received any offers of sponsorship because we think - Christo and I - that by now, they know we don't say yes, ever. So nobody even bothered." Asked about the proliferation of commercial imagery elsewhere in the city, Jeanne-Claude conferred briefly with her husband before she returned to the phone. "Christo answered, and I repeat word for word, 'I never think of advertising.' " Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

February 17, 2005

METRO MATTERS How Banners Navigated the Hurdles By JOYCE PURNICK FOR nearly three years, Vince Davenport has lived and worked in New York, planning and directing installation of "The Gates" in Central Park. He chose the materials, devised engineering solutions, negotiated with suppliers, selected contractors and dealt with park neighbors and a municipal hierarchy as muddled as rush-hour traffic. The project's engineer says he can't quite yet believe that he and his team pulled it off, but they did. And now seems a good time to ask what he thinks of New York. How tough did he find the city, once it finally gave the project the go-ahead? "It is a difficult place to work, but I don't think it's that difficult if you do it right," Mr. Davenport said yesterday. "Do your homework, and don't try to beat the system, but work with it. There are so many bureaucracies. Everybody wants to be in charge of their own domain, and I can understand that. But go through the hierarchy, sit down and draw a plan and present it - as opposed to trying to bulldoze your way through." With occasional exceptions, he didn't even find New Yorkers rude, said Mr. Davenport, a general contractor originally from Kansas City who sounds uncannily like another Missouri native, Harry S. Truman, and seems just as direct (if less crusty). Told that some who worked on the project say that they considered it to be his - becoming Christo and Jeanne-Claude's only when the saffron material was unfurled on Saturday - he chose different language, but acknowledged that the technical translation of the artistic design, the engineering, "was strictly mine." Though working in New York for the first time, he seems to have anticipated most problems, except one. Mr. Davenport said that while he fully expected New York to be expensive, he found that labor, trucking and parking were so much more expensive than he anticipated that the project's costs grew to more than $20 million from the $15 million he originally projected. What about that entrenched New York institution, bribes - what did they cost? "Not a dime," he said. "The suggestion was made a few times, 'Is there something we can do for you?' But never out and out, and I don't believe in it." Even for someone who's worked in Los Angeles and Berlin, the city's complexity sounds as though it was bewildering - the multiple rules from multiple agencies. "But I don't have a problem with it," continued Mr. Davenport, sitting in his trailer near the Boathouse yesterday morning. "To me, Central Park is the eighth wonder of the world - a gorgeous, beautiful park. I understand why you have to have so many rules. It's the only way, when so many people are coming into the park daily." IT was the rule not to disturb the park that complicated approval of the project, first proposed over a quarter-century ago and rejected. That was mostly because Central Park was in bad shape, partly because the park design called for making it worse by drilling 15,000 holes in the park to anchor the gates. When the artists decided to try again in 2002, Mr. Davenport told them: " 'This is impossible, I can't do this job.' I said the geology of the park will not allow you, even if you got permission, to drill simple six-inch-by-three-foot holes. You will wind up with a two-foot-diameter hole by the time you take out all the rocks you are going to hit." Even without having a solution, he recommended telling the city that the design would require no drilling. By that spring, he came up with an innovative design using heavy bases with anchor plates that serve as leveling devices to anchor the 7,500 vinyl gates. Doug Blonsky, president of the Central Park Conservancy, said yesterday that the revised design was "one of the most important factors that helped us change our feelings." Mr. Davenport, who had built tracks of houses and industrial buildings but is not a trained engineer, started working with Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1989, when a contractor-friend from Missouri, working on the couple's umbrella installation in the Los Angeles area, needed an associate with a California license. Mr. Davenport was licensed, and intrigued. He and his wife, Jonita, have been with the two artists ever since. The couple have been living on Manhattan's East Side since February 2002, but after "The Gates" closes in 10 days, they will return to their home in Leavenworth, Wash. "I'd love to stay," he said. "But I can't afford it." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You too could have a little Christo and Jeanne Claude in your home. http://www.not-rocket-science.com/media_gates.htm |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

New York Times

February 20, 2005 THE CITY Seeing Orange By TED CAPLOW HE exhibit that began last weekend in Central Park is many things to many people. For me and my beagle, Hazel, with whom I share a daily walk to work through the park, "The Gates" is just a distraction. What she wants to know is, where have all the squirrels gone? What I want to know is, from the standpoint of industrial ecology, how can Christo and Jeanne-Claude justify the environmental impact of this project? On their Web site, the artists, with apparent pride, declare that "The Gates" has required 10½ million pounds of steel, 60 miles of vinyl tubing and one million square feet of nylon fabric, plus thousands upon thousands of steel plates, bolts and nuts to hold the whole thing together. The plastic tubes and fabric are described as "recyclable," but no mention is made of the fate of the steel. According to the United States Department of Energy, the steel industry in this country consumes about 18 million B.T.U.'s of raw energy to produce one ton of steel. If the cast steel in "The Gates" is typical American steel, then making it has required 97 billion B.T.U.'s, an amount equivalent to the entire annual energy consumption - including that used to run cars, furnaces, air conditioners and home appliances - of nearly 500 New York state residents. Energy for the steel industry is supplied in roughly equal thirds by coal, natural gas and electricity from the grid. Based on generally accepted rates of carbon dioxide emissions for these three sources, it appears that making steel for "The Gates" churned out 7,000 tons of carbon dioxide, equivalent to the combined output of about 1,600 average American cars for a year (carbon dioxide is viewed by most scientists as a threat to the global climate system). We would have to plant more than 200 acres of trees and grow them for 10 years to remove this carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Central Park has an area of about 800 acres, but only part of this has trees; and the mature trees that dominate the park do not absorb carbon dioxide effectively, so we cannot look to the park to clean up the mess. In terms of sheer mass, the amount of plastic in "The Gates" is dwarfed by the steel, but emissions of carbon dioxide, dioxins and other toxins from plastics manufacturing are also a concern. The plastic chosen for the supports, polyvinyl chloride, or P.V.C., is an increasingly controversial material that releases dioxins and other carcinogens to the air and water during manufacture (and possibly afterward). Polyvinyl chloride has been singled out as "the poison plastic" by Greenpeace and other environmental groups. We now have 60 miles of it in the park. Clearly, the squirrels were not consulted on this choice. If the plastic used in "The Gates" is in fact recycled (Greenpeace warns of the "false promise" of polyvinyl chloride recycling, noting that only 1 percent gets recycled), some credit might be allowed, but at best this credit would account for only a fraction of the energy used and emissions produced. Nearly all steel is "recyclable," but the recycling rate (around 70 percent nationwide) is already accounted for in the energy intensity calculations above. More fundamentally, one cannot dismiss responsibility for the use of a primary material simply by claiming that this material could be reused. That's like claiming that no mink were harmed in making your fur coat, because you might donate it to good will someday. This is an unenlightened view of ecology. Why could the artists not have chosen a 100 percent postconsumer material, or better yet, a biologically derived material, to begin with? Such a choice would have reduced toxic emissions from the material itself, although we would still be left with the diesel trucks and propane forklifts scuttling to and from the park to carry this enormous mass in and out. It has also been loudly declared that the artists are paying for all of this out of their own pockets, through the sale of spinoff drawings and paintings to art collectors. These drawings can be viewed on the artists' Web site, and all share a pattern of coloration in which the city and the park, the buildings, the trees, the grass, are devoid of life, while the "The Gates" are portrayed in vivid color - the only objects of apparent interest to the artist. The setting could have just as easily been any other city, or no city at all, and little would change in the paintings. These depictions of a lifeless New York City are supposedly financing the materials, manpower and energy required to bring us "The Gates," but there is no mention of any fee paid for the pollution of the air and water, to say nothing of the threat to Hazel's squirrels. The choice of such an unfortunate orange hue - "saffron" to the artists, but to the rest of us more evocative of sanitation trucks, prison uniforms or road pylons - becomes clear: this is the color of hazard and danger. Hazel and I have chosen to interpret the whole business as an ecological warning sign. Ted Caplow, an environmental engineer, is the executive director of Fish Navy, a nonprofit organization that promotes sustainable technology. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/20/opinion/opinionspecial/20CIcaplow.html? Although The Gates are a nice distraction from the bitter Winter weather and leafless tree landscape, I agree with this op-ed. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Gates and employment

$21 Million…for what?

As one of the “paid volunteers” on Christo-Jeanne Claude’s The Gates, Central Park, New York City, the most frequent comment I heard was something about the $21 million that had been spent. While describing my experience on The Gates project to my husband, he commented that it was collectively realized. Bingo! Christo-Jeanne Claude’s art is always a project that involves hundreds, if not thousands, of people…people who help them bring that dream to reality. So now let’s talk about the $21 million. The people who help Christo-Jeanne Claude bring that dream to reality do not do it for free. There would be salaries for the project engineer, the project director, the project assistants, and the rest of Christo-Jeanne Claude’s team. And some of these people have been working over two years on this. But let’s get to the real nuts and bolts of the money – employing workers at the Gupta Permold plant outside of Pittsburgh who constructed the aluminum corner sleeves; employing workers at the ISG steel mill in Coatesville, PA who produced 5,290 tons of steel sheets for the base weights; employing workers at the C. C. Lewis steel plants in Conshohocken, PA AND in Springfield, MA who took the ISG steel sheets and turned them into the base weights; employing workers at the J. Schilgen Company in Emsdetten, Germany who produced the saffron, recyclable rip-stop nylon fabric; employing workers at Bieri-Zeltaplan in Taucha, Germany who cut, sewed and rolled the fabric panels and cocooned them with Velcro; employing workers at the North American Profiles Group plant in Holmes, NY who manufactured the vinyl poles; employing people who helped with the 10 containers shipped by boat from Germany; employing workers at the LMT-Mercer Group in Lawrenceville, NJ who produced the base plate covers, used to conceal the leveling plate. Now let’s add the employment of the truck drivers to get those materials from the New York Harbor, Pittsburgh, Coatesville, Conshohocken, Springfield, Holmes, Lawrenceville to the assembly plant in Queens, and the employment of workers at the assembly plant. And my guess is that was all before November 2004. Keep going? The workers who put down the base weights throughout Central Park were paid; more truck drivers were employed to bring the finished supplies from Queens to Central Park; and how about the bus drivers employed to take the paid volunteers to training sessions in Queens and to shuttle them back and forth in Central Park. And remember they’re paying for the extra security in Central Park, also. Then we could add in the food. From January 3rd to February 27th, all the workers in Central Park have been fed lunch every day, and coffee and pastry in the morning. Does YOUR boss do that for you? When an artist sells a piece of art, he employs 2 people – himself and the dealer. Christo-Jeanne Claude spent $21 million and my guess is that at least ½ to 2/3 of that went towards employing thousands of people. Hmmmmmmmm…art as employment. Maybe Christo-Jeanne Claude should be meeting with President Bush. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

February 14, 2005

METRO MATTERS It's a Park Whose Time Has Come By JOYCE PURNICK IT took nearly a quarter-century to bring Christo and Jeanne-Claude's "Gates" to Central Park. That does seem a bit extreme, even for New York. Why so long? Fortunately, it was easy to find out, because standing near the Sheep Meadow on Saturday morning, watching the curtains of cheerful saffron fabric being unfurled, was the very man who first said no, Gordon J. Davis. Mr. Davis, the former commissioner of parks and recreation, is now such a fan of the installation that he was wearing an orange hat and lapel ribbon. But in 1981, he called the original proposal "the wrong place, the wrong time." It called for a much larger installation and, unlike the current design, it would have left holes in the dirt and asphalt. The artists also wanted their show in the fall, rather than in winter. But those were not the main complications, Mr. Davis explained. "The basic reason was, the park was a disaster," he said. Central Park, hurt by the city's fiscal crisis, had deteriorated and was dangerous. The Central Park Conservancy, its privately financed savior, had only been founded in 1980. "My view was, there will be this wonderful thing for two weeks, and when it was gone people will look around the park and it will be a disaster," Mr. Davis said. "This time, the park has been completely revived, and it's a wonderful place." But back then, just imagine the public reaction to lavish spending - even of private dollars - on an artistic fancy in an otherwise shabby park. That would not have gone over well in a city where every decision has a political rationale. Today Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg's enthusiastic support for the project barely produced a ripple of dissent. If there really is a time for everything, this is the time for "The Gates." Spend a moment in the park and it's apparent. The installation has transformed the park into a public party. Like Operation Sail celebrating the bicentennial in 1976, or the fireworks commemorating the Brooklyn Bridge's 100th birthday in 1983, this is one of those moments in New York - the kind that gets people together to share something different, exuberant or in this instance, purely "preposterous," as Heather Tow-Yick put it yesterday in the park near Harlem. Ms. Tow-Yick, an assistant to the schools chancellor, quickly added, "I mean that in a fond way. It's classic New York." The apricot-tinged park this weekend seemed to mute the city's snarls, to grant a temporary respite from its insistent frustrations. Maybe "The Gates" is art, maybe it isn't. But it is uncomplicated fun to meet people from everywhere, to hear their stories and even become a fleeting part of them. Who could not smile at encountering Louise Kershaw and Glynn Moss of Manchester, England. Despite the winter weather, the young couple had decided to hold their wedding ceremony in Central Park, knowing nothing about "The Gates." The new husband and wife pronounced themselves delighted, if surprised. "Everyone's been wishing us well," said the bride, looking slightly dazed, as she and her husband posed for photographs near the Bethesda Fountain, surrounded by family and a friendly throng of strangers. THAT'S the story of the installation - the people, suggested Carl Petzhold, a retired writer from Hanover, Germany. In Berlin, where the same artists wrapped the Reichstag with fabric in 1995, "there were 5 million people, and they all excitedly talked to each other, and here is the same thing," said Mr. Petzhold, who came to New York with his wife, Sigrid, specifically to see "The Gates." "People will talk to you, no matter where you come from." Sophia Ginzburg of Albany, a medical technician, had a similar reaction. It is, she said, "like a holiday in here." Barbara Colon, walking her dog, Maxie, near West 104th Street yesterday was just happy to see more people in the park than usual, though many fewer than south of 96th Street. "And at last, they finally did something uptown," added Ms. Colon, who works in investment banking. The installation had its critics. But there is no doubt that the 16-day exhibit is a hit. Just as there was no doubt in 1981 that it would have been a dud. "E. B. White wrote that to live in New York you have to be lucky," said Mr. Davis, the former parks commissioner. "My corollary is, it's great to live in a city where you are allowed to change your mind." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

February 14, 2005 Park Visitors See Saffron, and Businesses See Green By JENNIFER MEDINA Dennis Roman hardly had a moment to look up at the towering orange frames snaking through Central Park, their saffron fabric waving in the Sunday sun. Not that he minded; he had hot dogs to sell. On a typical Sunday in February, Mr. Roman said, he usually makes about $100. By 3 p.m. yesterday, he had already taken in $1,000. "It's been like this all day," he said. "It's never like this usually, never." As the crowds flocked to the park yesterday to gaze at and ponder over "The Gates," the huge, colorful installation by Christo and his wife, Jeanne-Claude, businesses inside the park - from merchandise vendors to caricature artists to major restaurants - were booming. Parking garages nearby were filled and restaurants along the park's perimeter were packed with people jockeying for a table. City officials said they expected tens of thousands of people to show up for the exhibition, which is to be up for only 16 days, and whose $20 million cost is being borne exclusively by the artists. By the time the 7,500 gates are taken down in two weeks, the city expects to generate $80 million in business, with $2.5 million in city taxes alone, according to the city's Economic Development Corporation. The Strand bookstore's mobile stand, along Fifth Avenue near the southeast corner of the park, is normally closed from December to March, but decided to open because of "The Gates," according to a salesperson, Kevin Crow. He estimated that about 100 customers showed up on Saturday, 10 percent more than any other day. Books about "The Gates" and about previous projects of Christo and Jeanne-Claude made up most of the sales, he said. While business slowed "the tiniest bit" yesterday, Mr. Crow said, it was still considered a major success. Dozens of other vendors who would typically spend winter in business hibernation came out yesterday, prompted in part by the sunny skies. Stacey Berna, who makes and sells animal balloons for whatever customers are willing to pay, said she stayed home on Saturday, waiting to see how large the crowds would be and what the weather would bring. As she stood outside jacketless, she smiled at the sun and the crowds.. "This is just a lot of fun," she said, adding that she had about 150 customers by midafternoon. While she would typically see twice that in July, she was happy just to have a small bonus. "At this time of year, I'm home with my children," she said. She continued, "If it stays like this, it could be a busy couple of weeks." The Boathouse restaurant usually shuts its doors for dinner in the winter, but the general manager, Fonda Tsironis, said it would stay open every night during the exhibit. There was a two-hour wait for a table early last evening and it was already booked for tonight, Mr. Tsironis said. "We've been turning away people all day," he said, motioning to the tables full of brunch diners. "We love this, every minute of it. This is the kind of thing New York is made for." He estimated that about 40 percent of customers were tourists and that during the week the number of lunch diners would more than triple, totaling 250 to 300. With panoramic windows stretching across the dining room, Mr. Tsironis had plenty of occasion to look at the way the fabric swinging from the gates changed with the wind and the light. Christo and Jeanne-Claude had stopped by earlier in the day and received a standing ovation, but had not stopped to eat, Mr. Tsironis said. "I don't know where he's eating, or if he's eating," he said with a laugh. "He probably doesn't have time." Neither did the park's busy vendors, most of whom shrugged or laughed when asked what they thought of the spectacle that had brought out so many customers. "I don't really understand it," said Sharif Sadiq, a 45-year-old sketch artist from Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. He'd sold three caricatures by 4 p.m. and was hopeful he would sell a few more before nightfall. "Normally it's just one, so that's a major improvement," he said. "I just hope there are tourists, because city people don't usually come to buy this." Miguel Ixco was completely uninterested in discussing the finer points of art as he pulled out a thick stack of bills and counted his day's earnings from selling cotton candy. "It's not all that much," as he folded back $70. "But it's more than I'd usually have. There are so many people here, they have to buy something eventually." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

February 13, 2005 AN APPRAISAL In a Saffron Ribbon, a Billowy Gift to the City By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN Slide Show It is a long, billowy saffron ribbon meandering through Central Park -- not a neat bow, but something that's very much a gift package to New York City. "The Gates," by Christo and his wife, Jeanne-Claude, was officially unveiled yesterday. Thousands of swaths of pleated nylon were unfurled to bob and billow in the breeze. In the winter light, the bright fabric seemed to warm the fields, flickering like a flame against the barren trees. Even at first blush, it was clear that "The Gates" is a work of pure joy, a vast populist spectacle of good will and simple eloquence, the first great public art event of the 21st century. It remains on view for just 16 days. Consider yourself forewarned. Time is fleeting. On a partly sunny, chilly morning, with helicopters buzzing overhead and mobs of well-wishers on hand, an army of paid helpers gradually released the panels of colored fabric from atop the 16-foot-tall gates, all 7,500 of them. The shifting light couldn't have been better to show off the effects of the cloth. Sometimes the fabric looked deep orange; at other times it was shiny, like gold leaf, or silvery or almost tan. In the breeze, the skirted gates also appeared to shimmy like dancers in a conga line, the cloth buckling and swaying. Christo and Jeanne-Claude drove around slowly to watch the progress. Fans mobbed their car. Like all projects by this duo, "The Gates" is as much a public happening as it is a vast environmental sculpture and a feat of engineering. It has required more than 1 million square feet of vinyl and 5,300 tons of steel, arrayed along 23 miles of footpaths throughout the park at a cost (borne exclusively by the artists) of $20 million. I hadn't been quite sure when I first saw the project going up last week. From outside the park, the gates looked like endless rows of inert orange dominoes overwhelming Frederick Law Olmsted's and Calvert Vaux's masterpiece. But as the artists have insisted, the gates aren't made to be seen from above or from outside. I stopped in at a friend's office high above Central Park South yesterday and ogled the panorama, which was lovely. But it was beside the point. It's the difference between sitting in a skybox at Giants Stadium and playing the game on the field. The gates need to be - they are conceived to be - experienced on the ground, at eye level, where, as you move through the park, they crisscross and double up, rising over hills, blocking your view of everything except sky, then passing underfoot, through an underpass, or suddenly appearing through a copse of trees, their fabric fluttering in the corner of your eye. There are no bad locales for seeing them. But there are some spots at which the work looks best: around the Heckscher ball fields, where the gates are dense and lines of them swarm in many directions at once; at the base of Strawberry Fields, where two parallel rows march in tight syncopation; at Harlem Meer, where they cluster up to the shore and then clamber, helter-skelter, up the rocks. Also at Great Hill, near West 106th Street, where they encircle the crescent field, then descend a flight of steep steps. And at North Meadow, a wide-open vista, where the gates wander off toward the horizon, separating earth and sky with an undulating saffron band. People preened under the unfurled gates, watching the fabric sway. Now one no longer ambles through the park, but rather saunters below the flapping nylon. Paths have become like processionals, boulevards decked out as if with flags for a holiday. Everyone is suddenly a dignitary on parade. A century and a half ago, Olmsted talked about the park as a place of dignity for the masses, a great locus of democratic ideals, influencing "the minds of men through their imaginations." It's useful to recall that Christo conceived of "The Gates" 26 years ago, when Central Park was in abominable shape. The project had something of a reclamation mission about it, in keeping with Christo's uplifting agenda. He was born in Bulgaria in 1935 and escaped the Soviet bloc for Paris in 1958. His philosophy has always been rooted in the utopianism of Socialist Realism, with its belief in art for Everyman. But in place of the gigantic monuments of Mother Russia, forced upon the Soviet public and financed by the state, he has imagined a purely abstract art, open-ended in its meanings, paid for by the artist, and requiring the persuasion of the public through an open political process. After which the art comes and goes. "Once upon a time" is a phrase Christo likes. Once upon a time, he imagines people will say, there were "The Gates" in Central Park. Central Park is in fine shape today, but the project still has a social value, in gathering people together for their shared pleasure. Some purists will complain that the art spoils a sanctuary, that the park is perfect as it is, which it is. But the work, I think, pays gracious homage to Olmsted's and Vaux's abiding pastoral vision: like immense Magic Marker lines, the gates highlight the ingenious and whimsical curves, dips and loops that Olmsted and Vaux devised as antidotes to the rigid grid plan of the surrounding city streets and, by extension, to the general hardships of urban life. The gates, themselves a cure for psychic hardship, remind us how much those paths vary, in width, and height, like the crowds of people who walk along them. More than that, being so sensitive to nature, they make us more sensitive to its effects. We didn't need the gates to make us sensitive, obviously. Art is never necessary. It is merely indispensable. At its best, it leads us toward places we might not have thought to visit. Victor Hugo once said, "There is nothing more interesting than a wall behind which something is happening." This also applies to gates, which beckon people to discover what is beyond them. With their endless self-promotion, and followers trailing them like Deadheads from one global gig to another, it's no wonder that Christo and Jeanne-Claude have made a few skeptics of people who often have not seen their art at first hand. New Yorkers are a notoriously tough crowd. But I was struck by what I overheard a stranger say. She was a doubter won over yesterday. "It will be fascinating when they're gone," she mused. It took me a second to realize what she meant: that the gates, by ravishing the eye, have already impressed an image of the park on the memories of everyone who has seen them. And like all vivid memories, that image can take a place in the imagination, like a smell or some notes of music or a breeze, waiting to be rekindled. Once upon a time there were "The Gates." The time is now. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|