| New York

Architecture Images- Recent 515 West 23rd |

|

| Please note- I do not own the copyright for the images on this page. | |

|

architect |

Neil Denari |

|

location |

515 West 23rd |

|

date |

2012 |

|

style |

Blobitecture |

|

type |

Apartment Building |

|

construction |

Concrete and steel frame |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

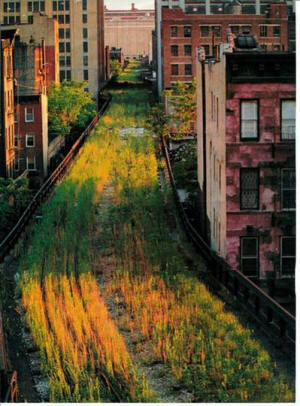

Top of the Line: Inside “that building” in the

middle of the city’s new attraction By Jason Sheftell The High Line has done as much for New York City horizontally as the Empire State Building has vertically. Arriving when millenniums meet, it may be the most important piece of income-generating, entertainment-oriented urban design since the boardwalk. Attracting over 40,000 visitors per weekend, it generates an estimated $2 billion in private investment. No public space has brought more people together in New York for positive reasons since the 1964 World’s Fair. Even on a Sunday at 9:30 p.m., people on the High Line gasp, smile and gaze. Couples kiss in the soft light. They dine. They flirt. They look up and down and across. They point and ask, “What’s that?” Recently, the most asked about topic on the High Line is a building. Rising like a pumped fist out of its center at 23rd St. and 10th Ave. is HL23, an 11-unit, 14-floor condominium where three-bedroom full-floor homes start at $3.45 million. You can’t miss it. It’s pure real estate porn, with 11-foot stainless steel panels on its eastern facade that ripple like water in the moonlight. Its front and back facades have window panels manufactured in China, some of which open at the touch of a button. Videos on YouTube show them being hung and clipped, one to classical music.  Structure and design are clear on HL23's front face, Rinze van Brug An architectural and technological feat, the building gets wider as it gets taller. Angled steel beams as thick as 8 inches hold it together with tapered pins that graphically spell out the building’s innards. An all-marble desk, weighing two tons and commissioned by HL23’s sales director, Erin Boisson Aries of Brown Harris Stevens, sits in its lobby. It was cut from one large stone. You can’t see it, but a glass box with sliding panels on the building’s roof serves as an extra living room for the penthouse, on the market for $12 million. The space now hosts arty events subtly marketing the property’s remaining eight condominiums. Three homes are in contract, with several offers on the table. Kanye West was allegedly interested in a home here. Before it was built, the Museum of the City of New York held an exhibition celebrating its design achievements. Since the completion, architectural critics have compared it to cars, airplanes, fishbowls and the American Dream. But sometimes a building is not just a building. This one has a story as important as its design, and there wouldn’t be one without the other.  A guest checks out a piece of furniture at an art exhibition at HL23. Steel beams hold the building together, allowing it to cantilever over the High Line (James Monroe Adams 4th) HL23 took six years from concept to completion, receiving seven zoning variances, one of which allowed it to be the only building to cantilever over the High Line. Held together by brute force, architectural technology and human persistence, the building was the subject of a legal challenge from a neighboring developer that stopped construction for nine months. It also survived the economic crisis. Through it all, developer Alf Naman carried the project on his back. A neighborhood landowner who knocked on West Chelsea doors looking for deals as a young real estate agent in the early 1990s, Naman calls it a “sculptural piece of art.” “I approached this as an artist would an installation piece,” says Naman, who developed the building with partner Garret Herer. “This was a complicated site and a complicated building. It basically sits on one leg and goes from 15 feet wide to 40 feet wide. To say this took fortitude is an understatement.”  A Sebastian + Barquet furnished 11th-floor home, $6.3 million (Rinze van Brug) Of course, Naman had help. City planner Amanda Burden conceived and secured those variances. Aries called HL23 one of the most satisfying “journeys” of her life. The building site and architect, though, perhaps had the most impact. Los Angeles-based Neil Denari designed HL23’s exterior and structure. Merging precision with sensuality, he knew because of the building’s location that he was giving New York a “new monument.” “This is a public building,” says Denari. “It’s in the middle of a city park. I don’t care if people are going to spend millions of dollars to live inside it. This building belongs to anyone who walks by. It’s not just another ego monument. I’m a site-specific architect, meaning the site drives what I design. Alf said to me right off the bat, ‘I want the building to get bigger as it goes up. Figure out how.’ Then he wanted it beautiful.” Esthetics are important to Naman, who lives more in the natural sunlight of the art world than the dark back offices of real estate. He understands complications in financial deals and construction delays. He has what most other developers do not — patience. “The challenge was staying the course,” he says. “I never doubted for a second that I had a responsibility to deliver something special to this site and to New York.” HL23 isn’t the tallest building in the city or along the High Line, nor is it the most expensive. But when you stand below it looking up, it’s almost as if you can touch the iron flesh and feel how sexy architecture can be when done right. It might have been a car, if this were Detroit in the 1950s. It might even have been a plane if Howard Hughes were in its cockpit. It could even be the American Dream, but a home in New York has become a global dream. Plus, we New Yorkers have our own dreams. Right now, those include survival, ingenuity and getting our “mojo” back. Without a city planning zoning ordinance that allowed nearby buildings to buy air rights from the High Line, HL23 and other nearby structures would exist only in an architect’s notebook. More than anything else, HL23 stands for commitment. It is a license to excel; a new bar for developers and architects intent on building anything important.  Collaborating architect Marc I. Rosenbaum calls this the split, the part of HL23 where the structure “tears away” from itself to create shape and views, Rinze van Brug. Along with the High Line that led to its creation, this building is a grueling championship season. It’s a comeback. It’s triumph. It’s the first time your kid says, “Mommy, I want to be an architect,” and you do whatever you can to help them do it. In the midst of our grief from 9/11 and our anger and disbelief that 10 years later not much has been built on that site while landowners argue over who pays for what, HL23 and the High Line remind us that it is time to heal. They remind us that we don’t have to be the tallest or the most perfectly shaped. And while metal bars hold us together, we don’t care if you can see right through us. Only in audacious New York do private residences co-exist with public space. In that way, HL23 is as much a part of our city as we are, and in some ways as human as a building can get with its own point of view. “If you love New York, how can you not want to undertake something challenging, interesting and rewarding for this city?” asks Naman. “This building is a kind of metaphor for why we’re here. We all want to push the envelope and be as good as we can. It’s easy to make money in the real estate game, but it’s painstakingly difficult to create something that will have lasting value. Everyone here was committed to that.” How do you sell this thing? Very carefully,” according to Erin Boisson Aries, senior vice president at Brown Harris Stevens, who’s in charge of sales at HL23. While Aries and company have thrown some broker events inviting top city agents with a high-net-worth clientele, the bulk of marketing has come from partnerships with art galleries and furniture boutiques.  Erin Boisson Aries (Anthony Lanzilote for News) For example, each floor currently for sale was modeled by a furniture expert or an art curator. An art exhibit on the building’s 10th floor was curated by Sandra Antelo-Suarez, the founder of the avant-garde art collective Trans>. One work by Zilvinas Kempinas is a high-powered fan that keeps magnetic tape shaped in a perfect circle elevated against a wall. In another, a pair of black porcelain boots by David Shrigley sit on the floor. All layouts and finishes were handled by Thomas Juul-Hansen, who designed eye-popping all-marble bathrooms. Model units are filled with one-of-a-kind objects from local furniture dealers Magen H Gallery and Sebastian + Barquet. “This is such a unique building that buyers needed to see the finished product,” says Aries, who never considered lowering prices. “We only have 11 homes. Buyers will see there is no place in the world to live like this.”  (James Monroe Adams 4th) And the marble desk (shown above) in the lobby that weighs 2 tons? “That’s a piece of art in itself,” she says. “Size matters sometimes.” Source- http://bestplaces.nydailynews.com/stories/top-line-inside-building-middle-citys-new-attraction --------------- Notes I remember when the renderings for this first came out. Not surprisingly, it only featured the building’s “good side.” Looking at it in pictures I can see why– from the three other sides it looks like crap. Interiors look nice, though– avoided that museum gallery/college dorm/ hotel room look. The perfect building for a rich exhibitonist – flasher ! A tad too weird for most of us, but reminds one of that Crystal Cathedral in Calif. that went broke recently, and is up for sale. If you dream of living in a greenhouse, this could be your moment. |

|

|

|

|

|

HL23 architect Neil Denari spoke about his East Coast

comeback, his shiny buildings that look like cars, and what makes his High

Line building a "social contract." The best part may be the archibabble that

results from a question about building luxury residences: "Okay, this is a

very high-end building, it's very expensive, but I think for me, I just sort

of think it's for the city. And the people who live in this building, I

think they know the building is for the city. They're participating in the

symbiosis of the High Line and the shift in design culture. New York is

back." Neil Denari |

|

|

|